8 R Markdown

8.1 Introduction to R Markdown

This page will guide you through creating and editing R Markdown documents. This is a useful tool for reporting your analysis (e.g. for homework assignments). Of course, there is also a cheat sheet for R-Markdown and this book contains a comprehensive discussion of the format.

The following video contains a short introduction to the R Markdown format.

Creating a new R Markdown document

In addition to the video, the following text contains a short description of the most important formatting options.

Let’s start to go through the steps of creating and .Rmd file and outputting the content to an HTML file.

If an R-Markdown file was provided to you, open it with R-Studio and skip to step 4 after adding your answers.

Open R-Studio

Create a new R-Markdown document

Save with appropriate name

3.1. Add your answers

3.2. Save again

“Knit” to HTML

Hand in appropriate file (ending in

.html) on learn@WU

Text and Equations

R-Markdown documents are plain text files that include both text and R-code. Using RStudio they can be converted (‘knitted’) to HTML or PDF files that include both the text and the results of the R-code. In fact this website is written using R-Markdown and RStudio. In order for RStudio to be able to interpret the document you have to use certain characters or combinations of characters when formatting text and including R-code to be evaluated. By default the document starts with the options for the text part. You can change the title, date, author and a few more advanced options.

The default is text mode, meaning that lines in an Rmd document will be interpreted as text, unless specified otherwise.

Headings

Usually you want to include some kind of heading to structure your text. A heading is created using # signs. A single # creates a first level heading, two ## a second level and so on.

It is important to note here that the # symbol means something different within the code chunks as opposed to outside of them. If you continue to put a # in front of all your regular text, it will all be interpreted as a first level heading, making your text very large.

Lists

Bullet point lists are created using *, + or -. Sub-items are created by indenting the item using 4 spaces or 2 tabs.

* First Item

* Second Item

+ first sub-item

- first sub-sub-item

+ second sub-item- First Item

- Second Item

- first sub-item

- first sub-sub-item

- second sub-item

- first sub-item

Ordered lists can be created using numbers and letters. If you need sub-sub-items use A) instead of A. on the third level.

1. First item

a. first sub-item

A) first sub-sub-item

b. second sub-item

2. Second item- First item

- first sub-item

- first sub-sub-item

- second sub-item

- first sub-item

- Second item

Text formatting

Text can be formatted in italics (*italics*) or bold (**bold**). In addition, you can ad block quotes with >

> Lorem ipsum dolor amet chillwave lomo ramps, four loko green juice messenger bag raclette forage offal shoreditch chartreuse austin. Slow-carb poutine meggings swag blog, pop-up salvia taxidermy bushwick freegan ugh poke.Lorem ipsum dolor amet chillwave lomo ramps, four loko green juice messenger bag raclette forage offal shoreditch chartreuse austin. Slow-carb poutine meggings swag blog, pop-up salvia taxidermy bushwick freegan ugh poke.

R-Code

R-code is contained in so called “chunks”. These chunks always start with three backticks and r in curly braces ({r} ) and end with three backticks ( ). Optionally, parameters can be added after the r to influence how a chunk behaves. Additionally, you can also give each chunk a name. Note that these have to be unique, otherwise R will refuse to knit your document.

Global and chunk options

The first chunk always looks as follows

```{r setup, include = FALSE}

knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = TRUE)

```It is added to the document automatically and sets options for all the following chunks. These options can be overwritten on a per-chunk basis.

Keep knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = TRUE) to print your code to the document you will hand in. Changing it to knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = FALSE) will not print your code by default. This can be changed on a per-chunk basis.

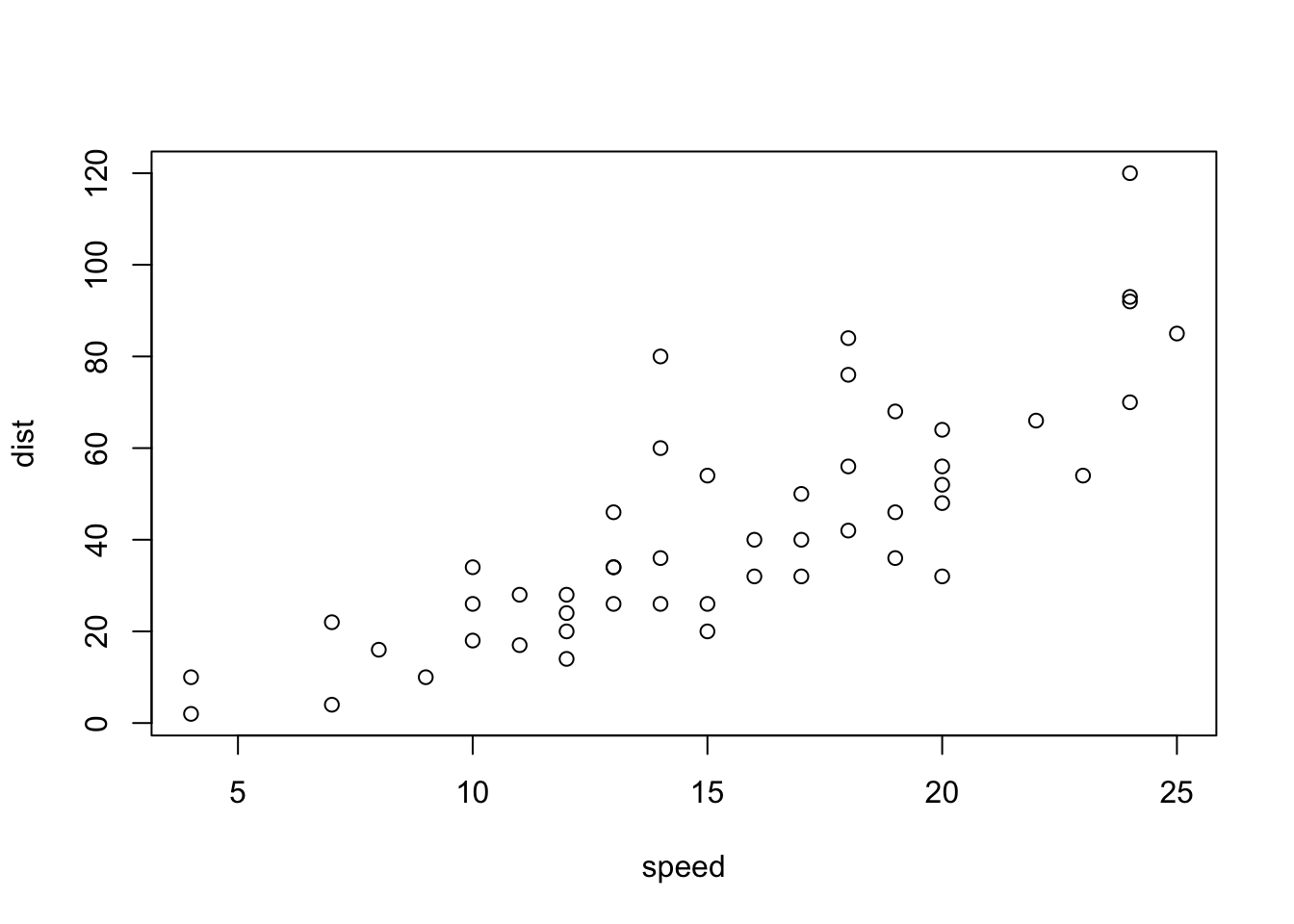

```{r cars, echo = FALSE}

summary(cars)

plot(dist~speed, cars)

```## speed dist

## Min. : 4.0 Min. : 2.00

## 1st Qu.:12.0 1st Qu.: 26.00

## Median :15.0 Median : 36.00

## Mean :15.4 Mean : 42.98

## 3rd Qu.:19.0 3rd Qu.: 56.00

## Max. :25.0 Max. :120.00

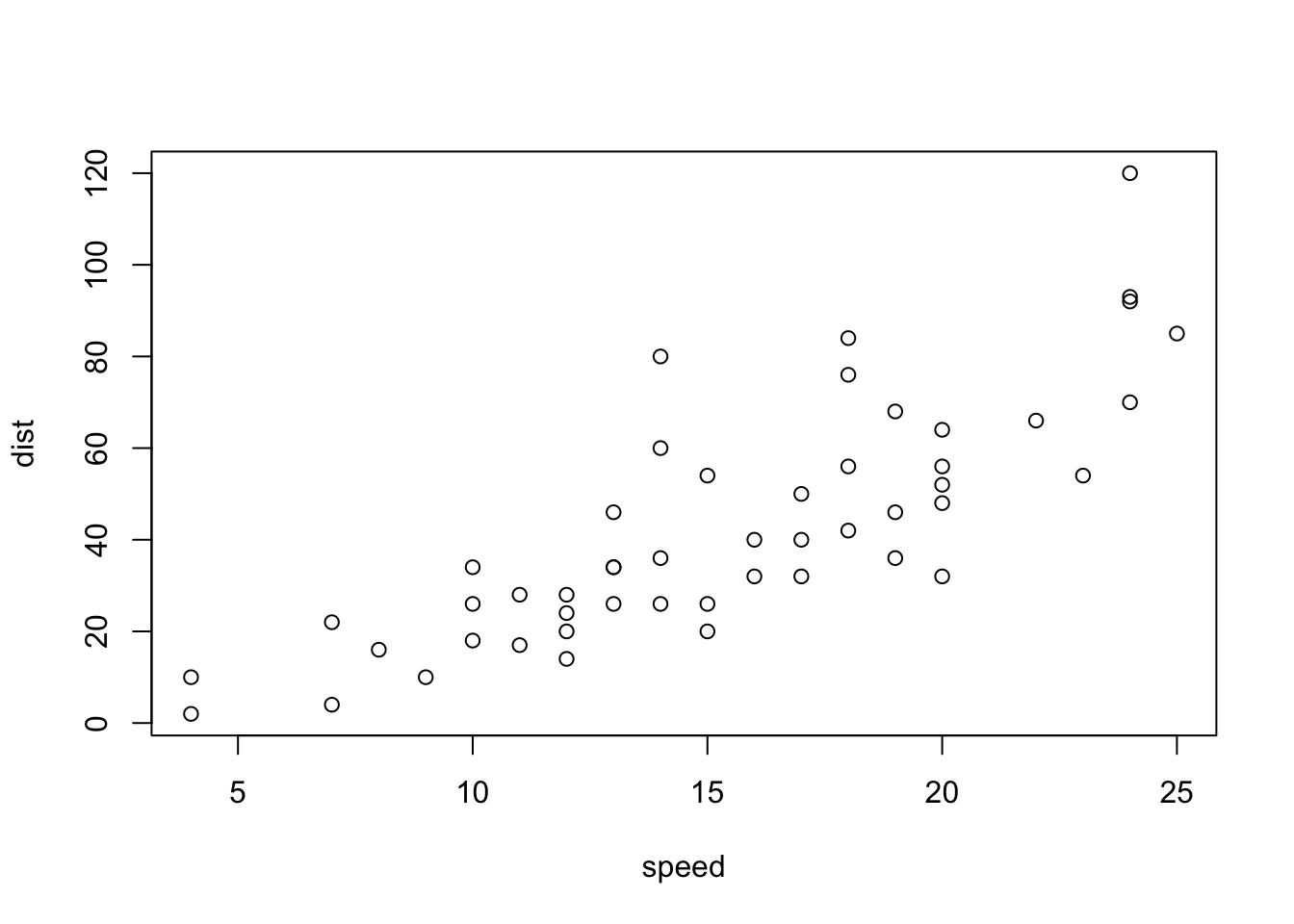

```{r cars2, echo = TRUE}

summary(cars)

plot(dist~speed, cars)

```## speed dist

## Min. : 4.0 Min. : 2.00

## 1st Qu.:12.0 1st Qu.: 26.00

## Median :15.0 Median : 36.00

## Mean :15.4 Mean : 42.98

## 3rd Qu.:19.0 3rd Qu.: 56.00

## Max. :25.0 Max. :120.00

A good overview of all available global/chunk options can be found here.

LaTeX Math

Writing well formatted mathematical formulas is done the same way as in LaTeX. Math mode is started and ended using $$.

$$

f_1(\omega) = \frac{\sigma^2}{2 \pi},\ \omega \in[-\pi, \pi]

$$\[ f_1(\omega) = \frac{\sigma^2}{2 \pi},\ \omega \in[-\pi, \pi] \]

(for those interested this is the spectral density of white noise)

Including inline mathematical notation is done with a single $ symbol.

${2\over3}$ of my code is inline.

\({2\over3}\) of my code is inline.

Take a look at this wikibook on Mathematics in LaTeX and this list of Greek letters and mathematical symbols if you are not familiar with LaTeX.

In order to write multi-line equations in the same math environment, use \\ after every line. In order to insert a space use a single \. To render text inside a math environment use \text{here is the text}. In order to align equations start with \begin{align} and place an & in each line at the point around which it should be aligned. Finally end with \end{align}

$$

\begin{align}

\text{First equation: }\ Y &= X \beta + \epsilon_y,\ \forall X \\

\text{Second equation: }\ X &= Z \gamma + \epsilon_x

\end{align}

$$\[ \begin{align} \text{First equation: }\ Y &= X \beta + \epsilon_y,\ \forall X \\ \text{Second equation: }\ X &= Z \gamma + \epsilon_x \end{align} \]

Important symbols

| Symbol | Code |

|---|---|

| \(a^{2} + b\) |

a^{2} + b

|

| \(a^{2+b}\) |

a^{2+b}

|

| \(a_{1}\) |

a_{1}

|

| \(a \leq b\) |

a \leq b

|

| \(a \geq b\) |

a \geq b

|

| \(a \neq b\) |

a \neq b

|

| \(a \approx b\) |

a \approx b

|

| \(a \in (0,1)\) |

a \in (0,1)

|

| \(a \rightarrow \infty\) |

a \rightarrow \infty

|

| \(\frac{a}{b}\) |

\frac{a}{b}

|

| \(\frac{\partial a}{\partial b}\) |

\frac{\partial a}{\partial b}

|

| \(\sqrt{a}\) |

\sqrt{a}

|

| \(\sum_{i = 1}^{b} a_i\) |

\sum_{i = 1}^{b} a_i

|

| \(\int_{a}^b f(c) dc\) |

\int_{a}^b f(c) dc

|

| \(\prod_{i = 0}^b a_i\) |

\prod_{i = 0}^b a_i

|

| \(c \left( \sum_{i=1}^b a_i \right)\) |

c \left( \sum_{i=1}^b a_i \right)

|

The {} after _ and ^ are not strictly necessary if there is only one character in the sub-/superscript. However, in order to place multiple characters in the sub-/superscript they are necessary.

e.g.

| Symbol | Code |

|---|---|

| \(a^b = a^{b}\) |

a^b = a^{b}

|

| \(a^b+c \neq a^{b+c}\) |

a^b+c \neq a^{b+c}

|

| \(\sum_i a_i = \sum_{i} a_{i}\) |

\sum_i a_i = \sum_{i} a_{i}

|

| \(\sum_{i=1}^{b+c} a_i \neq \sum_i=1^b+c a_i\) |

\sum_{i=1}^{b+c} a_i \neq \sum_i=1^b+c a_i

|

Greek letters

Greek letters are preceded by a \ followed by their name ($\beta$ = \(\beta\)). In order to capitalize them simply capitalize the first letter of the name ($\Gamma$ = \(\Gamma\)).